After the work is done, the team reflects on the last twelve weeks.

Team meeting: Adjourning

During our final team meeting, I proposed that we cover the following points:

- Reflect on the success of our project

- Review our team performance using the list contained in our team charter.

- (Optionally) Prepare goals for futher self-improvement.

These are based on a proposed fifth stage to Tuckman’s small group development model – the adjourning stage, which helps provide teams with closure after a period of working together (Tuckman and Jensen 1977).

Reflecting on our success

Overall, as a team, we were very happy about the results of our work. Some of the points that specifically involved my contribution were:

- We knew that some teams struggled with making decisions quickly, but we were well organised enough to avoid that.

- The videos are made to a high standard, and we are proud to display them to others.

- We delivered on the promise of simulating a team environment using real-world tools and techniques (Jira, Scrum, source control).

I also talked about the more difficult parts of the experience:

- I felt that the game ended up without a strong (innovative) core gameplay loop. I would have preferred that we either spent more time working on the concept, or used the first prototype to draw informed conclusions and build a second one. However, as we were time constrained, I conceded that moving on from the design stage to building and refining our present concept was ultimately a good decision, as ultimately it mattered more for the final pitch.

- In a real world scenario, I would be more comfortable spending more time ensuring that the core gameplay is solid and innovative.

- Other team members expressed that not every game needed a strong, original core concept and could sell well by imitating existing, successful mechanics.

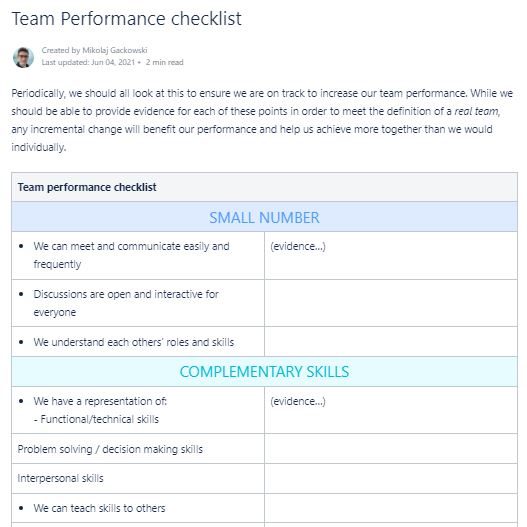

Team performance checklist

The checklist, which I prepared in week 1, is borrowed from the Team Basics section of The Wisdom of Teams (Katzenbach and Smith 2015 : 58-61). It had since been incorporated into our team charter as a way to measure our performance.

Small number

We unanimously agreed that the methods we chose to communicate – primarily Discord and Miro – allowed us to comfortably communicate and contribute. While technical issues occasionally manifested (such as connectivity issues from myself and Paul), there was always a way to ensure that our opinions were articulated and considered.

Complimentary skills

We had a strong mix of different types of skills. While funcional skills were contributed by individuals (e.g. James – programming, Paul – modelling), problem-solving and interpersonal skills were required and frequently demostrated by each member as part of our day to day work. I took upon myself as team leader to make decisions around organisation and scheduling, but small and large decisions were made by each member while working within their individual domains. We maintained friendly and professional relations with our supervisor, and contractor (voice actor).

There were numerous instances where one team member taught skills to another – e.g. James teaching version control, me presenting Confluence/Jira etc. Finally, we all confirmed that we kept acquiring new domain specific skills as part of the project – in my case, it was the basics of working with new software such as Unreal Engine and Ableton.

Meaningful purpose

In retrospect, we could say that the purpose of our prototype was to spread awareness about dementia. While we were all aware of this goal, it did not constitute a driving force behind our development, and therefore we were unable to find sufficient evidence to assert that this was truly our “meaningful purpose”.

Instead, the purpose (as our team charter defined it) which we did frequently reiterate in meetings was the desire to create a stunning portfolio piece and help us advance our careers. While not strictly a team purpose, it could be argued that it would have been impossible to achieve in the timeframe without teamwork.

Specific goals

We fared better here, having an upfront goal to create a prototype that could be pitched to a publisher. We had concrete work-products (deliverables), a mechanism to prioritise and ability to work in milestones to achieve small wins (Scrum + Jira tasks).

While those small tasks were generally specific and well defined, we agreed that our main goal (prototype that could be pitched to a publisher) was more ART than SMART. That is, while attainable, relevant and time-based, its definition was neither particularly specific nor measurable.

Common approach

At first, there was significant anxiety to spend most of our time on hands-on work. Over time, the team warmed up to our team meetings and procedures and saw the value in them. As we introduced sprints, we began to normalise, spread workload equally, and look back on the amount of work done easily.

We can emasure the successful result by looking at our Velocity report – evidencing that, as time went on, our work output increased.

Mutual accountability

The team was eager to pick up tasks to ensure that we could succeed as a team, regardless of whether those tasks were originally assigned to a specific member. For example, during Matt’s absence, James helped edit down his presentation script. In that sense, there was a feeling that “only the team can fail”.

In general, because of eveyone’s commitment, access to 24/7 communication and the practice of taking meeting notes, we found ourselves in an environment where micromanagement, or penalising members, were unnecessary. There was a sense of trust that we were all working for the team’s success.

Summary

I was happy to see how my contributions to the team’s organisation and processes enabled many of the successes evidenced in the checklist.

While we could comfortably talk about having a small number, complimentary skills, common approach and mutual accountability, we were not entirely purpose or smart goal driven as defined in Katzenbach and Smith’s book. Perhaps the existence of an externally imposed deadline, marking rubric and requirement for a theme diminished the need for developing an internally motivated team purpose. Our individual goals however (the desire to improve our skills) were more than enough to drive us forward.

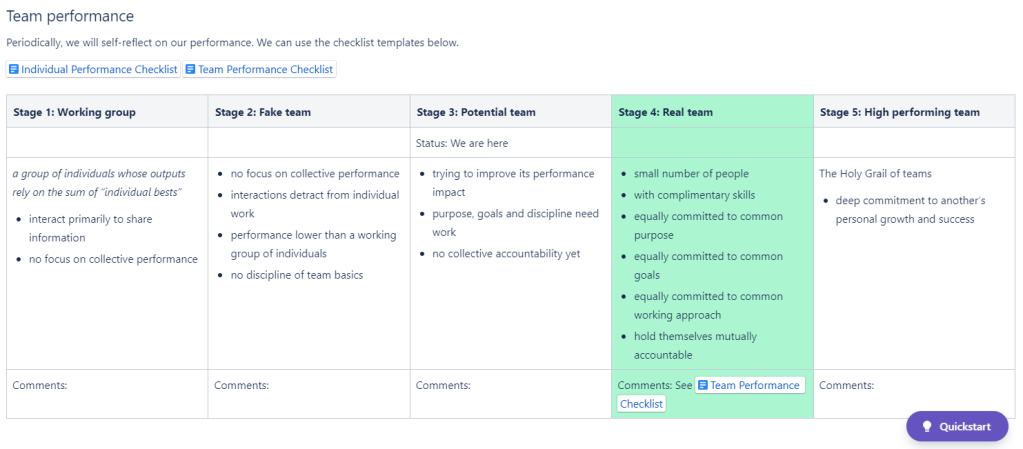

On the Confluence home page of our project, I kept a table that we could use to track how far along our team on the path from a “Fake”/”Potential team” to a high-performing team. At the end of the meeting, we were happy to “upgrade” this to “Real team” based on the evidence we gathered.

Personal goals

In-engine improvement

At the beginning of the module (as well as during the interim retrospective) I outlined a few personal goals for this module, one of which was to spend time with Unreal Engine 4 and gain more experience using it.

In the end, other priorities – team lead activities, research – made it so that much of the work in-engine was done by other members, and if I wanted to get hands-on experience, I would need to find a self-contained area to work within as to not interrupt their process. That area turned out to be audio.

Coming into the module with no prior experience in Unreal Engine, I started my journey with tutorials and documentation, but it was the goal of creating an ambient soundscape that focused my efforts. While I was focused on solving specific problems – such as creating the right attenuation shape for each object (attenuation defines how the souds changes its properties as we change distance from it) – I got steadily more familiar with the interface, key bindings, and camera controls.

Ultimately, I ended up not implementing any logic – there simply wasn’t enough time and it wasn’t the best use of our team’s resources. It was nevertheless a fine introduction to the engine, witnessing how our level grew bigger and more complex.

Team leader role

During the first week of the module, I took part in a challenge activity that involved taking personality tests. The result of the Enneagram test described me as a Peacemaker – “someone who likes to keep a low profile and let people around them drive the agenda” (Truity Psychometrics 2014). This module, I had the opportunity to try a team leader role and verify that result.

I admit that parts of this role have been stressful experiences – particularily in the beginning, when I felt that imposing structure would be interpreted by the team as holding us back. However, I felt that the biggest difficulty I’ve had was with finding the balance between being a team leader and a team member.

I feel that if someone else had taken the role, I could have focused more on my own personal goals – working in-engine, for example. This makes sense to me, as one of a leader’s roles is to remove distractions from other team members. Had I been fully committed to just organisation, decision making, and planning, I suspect much of my stress would be gone.

Feedback from the team about my performance has been positive, to my great relief. One constructive piece I received from Matt was that my mode of working was quite consciencious which consumed a lot of my time, and therefore I would benefit by allowing myself to spend more time realising my personal goals.

References

KATZENBACH, Jon R and Douglas K SMITH. 2015. The Wisdom of Teams : Creating the High-Performance Organization. Boston: Harvard Business Review Press.

TRUITY PSYCHOMETRICS. 2021. “The Enneagram Personality Test.” Truity [online]. Available at: https://www.truity.com/test/enneagram-personality-test [accessed 23 Aug 2021].

TUCKMAN, Bruce W. and Mary Ann C. JENSEN. 1977. “Stages of Small-Group Development Revisited.” Group & Organization Studies 2(4).