Fig 1. Original concept art for Rhythm Dice from 2021.

Less than two years ago, I decided that I would learn how to make games. In truth, I had made that decision far longer ago, and far from once or twice. This was however the moment when I committed a significant part of my time to the practice by joining a Masters program. In a year and a half of part-time study, I submerged myself in design theory, and produced a number of prototypes. Eventually I was ready to commit to making a small, finished game.

The goal of finishing and releasing a game, no matter how small, is important to me for a number of reasons. Firstly, I believe that there is much to learn from the experience of releasing a game. By making prototypes never intended to be released to a wider audience, it is easy to re-tread the same familiar ground of design and development, without ever having to engage fully with polishing and QA. Secondly, the experience of having released a title is often recognised, and sometimes required, by fellow game developers looking for employees and contractors to work with. Finally, I consider it to be a personal and professional milestone.

What follows is a series of blog posts that summarise my progress on a six-month project where I make a game. Blogging gives me an opportunity to organise and filter my research notes, and to provide evidence for my involvement in the project. By making those posts public, I also hope that some of the research and techniques might end up being useful to others.

Although this is a personally driven project, I am working on it as part of a Masters course. Therefore, I will benefit from having weekly group webinars, one-to-one supervisor meetings, access to a number of libraries as well as a forum of fellow practicioners.

The academic setting also necessitates that my practice is underpinned by rigorous research, and the game’s development will be instrumental in answering a research question. In the first weeks of the project, I will explore what that question should be.

Structure

The project lasts from late January until mid-August 2022, and is divided into three-week sprints.

I dedicated this first sprint to envisioning – exploring available research to determine the best

Selecting the research question

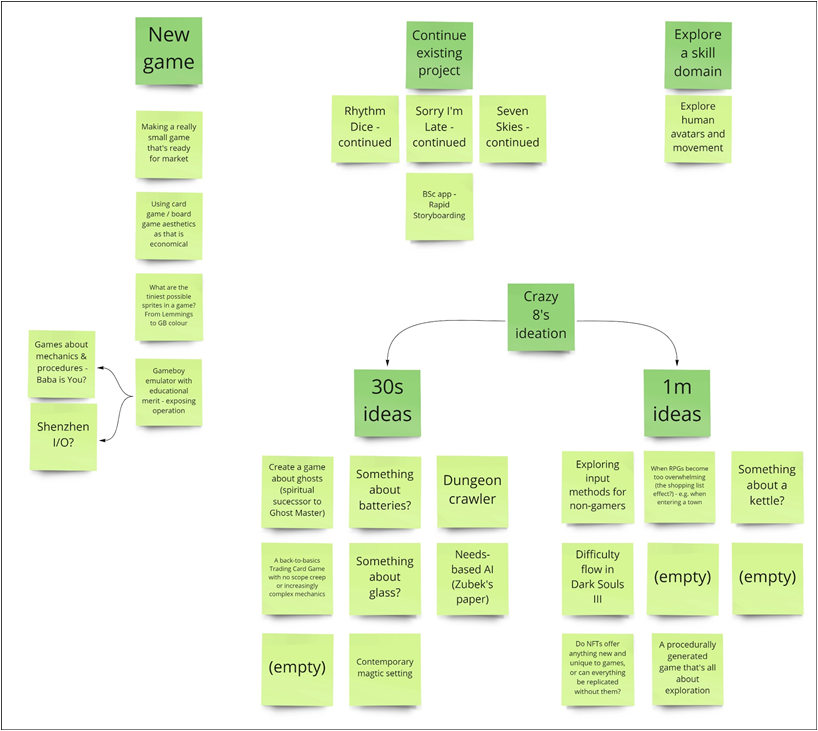

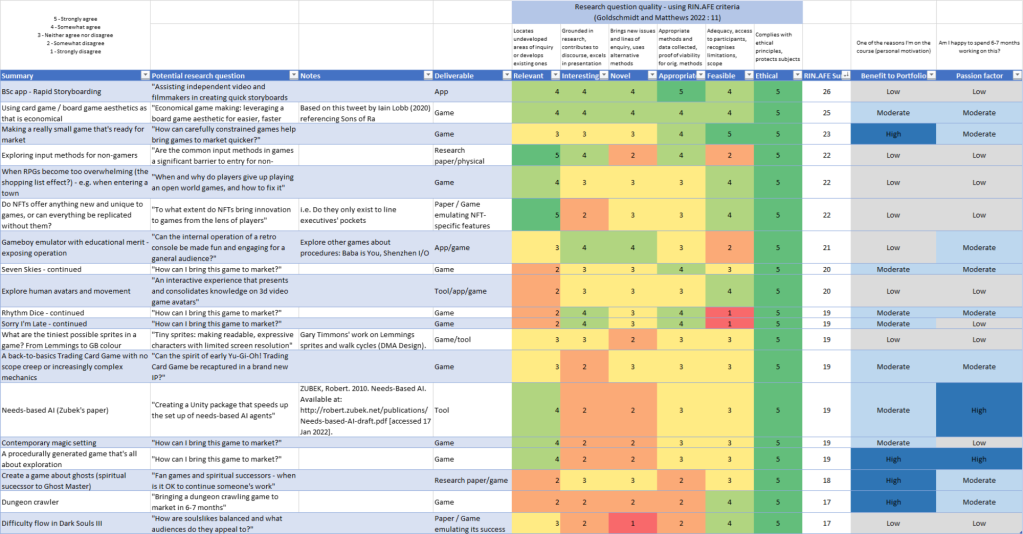

While I was coming up with a large quantity of research topics, I found it difficult to select one, and felt that I was in need of a more objective approach. When browsing through existing research, I found a set of criteria originally developed to assess quality of research questions in the medical field (Goldschmidt and Matthews 2022):

After evaluating my research topic options on a spreadsheet, with my research supervisor’s advice, I chose to explore the idea of using board game design techniques as a way to make game development more economical (at this stage, with focus on aesthetics). The topic first occurred to me when reading the tweet by Iain Lobb (2021):

The chosen topic seemed to work well with my goal of being able to finish the development of a game, as the research findings could potentially be used to reduce scope and maximise the chances of finishing it within the project’s duration.

Initial research

Greg Grimsby’s GDC 2021 talk, Art Direction for Board Games: Creating Compelling and Effective Visual Designs, was an excellent start to the research. The key relevant points being:

- We can imagine functional-only art design and heavily embellished aesthetics as two ends on the same continuum. It’s the artist’s job to decide how much sparkle to add without hindering communication. There is considerable wiggle room in that aspect.

- Signal versus Noise is important – not every surface needs to be textured.

- ‘Abstract games’ are a gameplay genre, and do not necessarily need to have simple, abstract aesthetics – they can be beautiful too (see: Santorini) (Grimsby 2021).

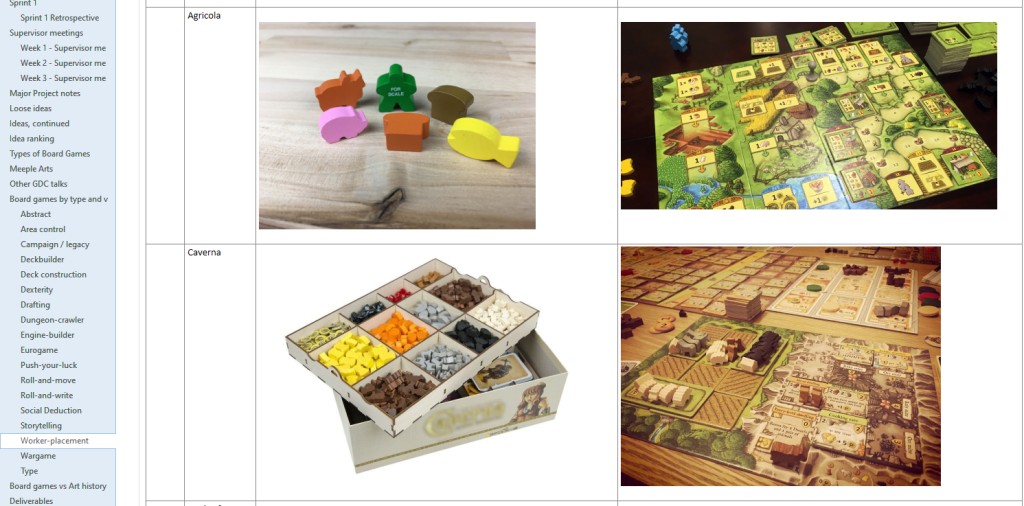

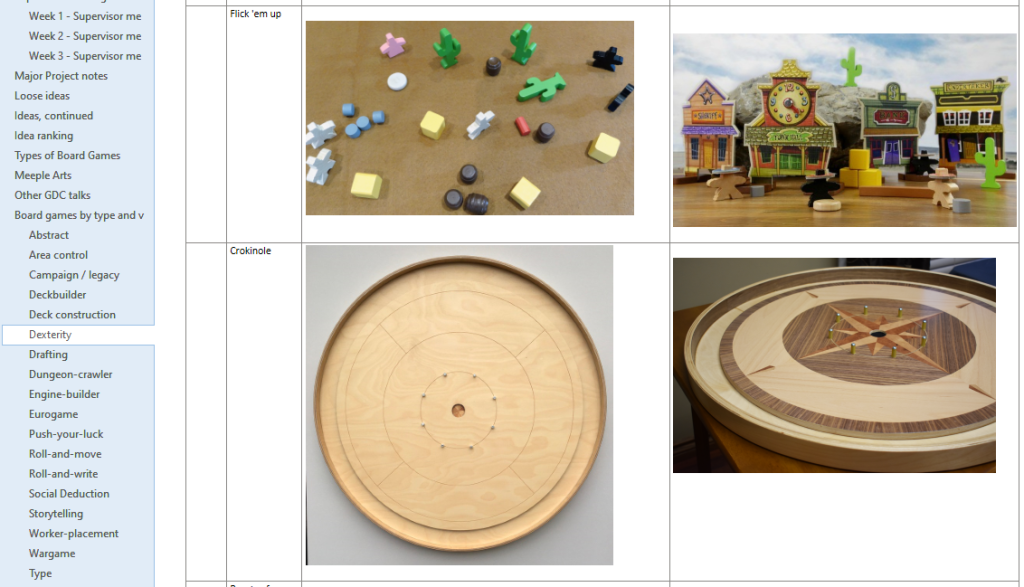

The talk is of course much longer and covers other excellent topics, but from here I could already launch an initial investigation: if aesthetics are on a spectrum, are there any patterns to recognise? Perhaps when we slice board games by genre? Simon Castle offers a convenient classification of board game genres (2020), which greatly helped in creating a sort of ‘mood board’ of board game examples.

Comparing versions and or different elements from 67 different board games, some patterns did emerge:

- Anything flat, typically game boards and cards, tend to feature lavish embellishments. This, according to Grimsby, is what the market expects (2021). It is actually rare that a flat surface isn’t covered with art, with the exception of some games featuring minimalist art.

- 3D pieces more often come in the form of simple geometric shapes, or meeples. Hypothesis: this might be driven by economics, perhaps logistics (generic shaped blocks are produced en masse). And it prompts the following question: how does that compare to the availability of 2D and 3D assets for the purposes of game production? How ‘generic’ are typical asset store models?

- Wargames, area control games and dungeon crawlers in particular feature more detailed player figurines.

- In the case of Warhammer, for example, producing distinctively shaped figurines and requiring them to play the game turned out to be a lucrative business.

- Outside of that, what do these games have in common? Does roleplay play a more important element?

In any case, while those questions would be interesting to research, I wanted to circle back to my original goal – to see if my research question could be narrowed down to a particular board game genre. I was certainly under the impression that the most interesting findings were waiting for me outside of just the realm of abstract games, and so for the moment decided not to reduce the scope of my research. Should the problem domain become overwhelming in the future, I have the option to filter out certain games.

And so, my research question at the moment is:

How can board game production techniques be used to make video game production faster?

Planned deliverables

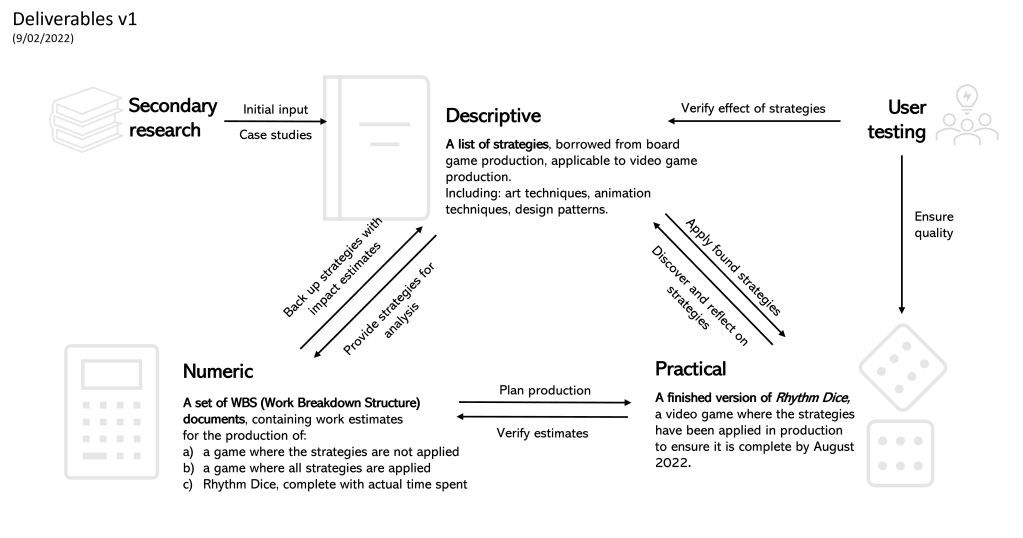

By August, I thought I would have the following:

Considering the ambitious scope however, here is a revised version that emphasizes the practical work element:

What is Rhythm Dice?

Rhythm Dice is a prototype I developed during a previous 12-week university module. It’s a rhythm-based game that has the player control a die through an obstacle course, on a quest to complete a collection of different game pieces.

The prototype’s development process was documented extensively in these posts.

The game received positive feedback from peers and was considered to have commercial viability. Therefore, I chose it as the basis for the six-month project’s practical work element. The goal is to have the game in a finished state by the end.

However, the game’s original scope would have been too large to manage within this time (regardless of whether board game-inspired strategies were implemented or not). And so, I reviewed the results of the original playtesting sessions and, as well as the game’s original pillars (forming the central theme: ‘the thrill of the chase’), to help me decide what to leave on the cutting room floor.

| Original vision | Reduced scope | Notes / justification |

| Two main settings: game shop and gameplay (magical reality) | Game shop reduced to single screen centered on the player’s collection (e.g. Rewards now unlocked directly on collection screen). Game also launched from collection screen. | Simply a condensed version of the original vision – appropriate since the game will likely be shorter. |

| A “hero’s journey” arc delivered through introduction of mechanics and environmental storytelling (posters, cards) | Cut | Requires a fair amount of custom level designand scripting which are time-consuming |

| 6 themed levels with 12 fictional board games | A single auto-generated endless level with a neutral theme (alternatively: autogenerated levels with a increasing difficulty parameters). | Simple way to reduce scope, with shorter length compensated for with replayability. The game may become more similar to a roguelite like Crypt of the Necrodancer. |

| 6 collectable enemies per board game = 72 enemies total | 24 pieces which can be either: – organised into 6×4 sets (more focused collecting, but feeling of “only” 4 sets) – unorganised (drop a resource that can be exchanges for pseudorandom rewards) | Let’s say the game is 2h long and we want the player to spend 5 minutes on average between encountering a new piece – that’s 24 pieces. |

| A set of “boss” enemies based on fantasy archetypes | Cut | Less meaningful without the story arc. |

| 6 alternative dice designs as rewards | 5 + 1 starting design | Not significantly reduced as those designs are simple to make and implement |

| 6 alternative dice materials as rewards | 5 + 1 starting design | Not significantly reduced as those materials are simple to make and implement |

| 6 musical themes for die movement and interactions | Music continues to be varied: a minimum of three musical themes for movement tones and combat chords, one of them being jazz. | The musical element (jazz) was a well received element of the original prototype, with a request for more variety |

| Conquered enemies stored in named collection box | Retained – important for long-term goals and the collector’s fantasy. Unlocks after first run. | The ‘unlocking’ is a quick way to reintroduce some of the progression that was removed with the story arc. |

| Diorama mode unlocked for beating the game | TBC – best determined during playtesting. Reserve effort to implement some completion reward. | No story to beat, but collection of enemies can be fully completed. Diorama mode was expensive to implement, so perhaps user testing can reveal players’ fantasies, while future development reveals what features can be added at little cost. |

| A ‘thrill of the chase’ fantasy: “I want a collection of nerdy trinkets” + “I want to find ways to obtain stuff” + “I want RPG-like encounters”. | Retained | |

| + Any strategy discovered via research could be applied to help reduce development effort |

Table 1. Original notes used in reducing the scope of Rhythm Dice.

I also made sure to clearly define the scope of the other deliverables (supplementary materials):

| Scope | Notes / justification |

| Strategies learned from board game production to be applied to video game production: | |

| A list of potential strategies where each has a source (either secondary or practice-led) and a short description (1-2 sentences). Number of entries on list depends entirely on results of research. | Minimal effort which is essentially equivalent to documenting research (i.e. recommended anyway). |

| Of the list above, the 3 most promising will be applied to the development of Rhythm Dice. Their entries will be expanded upon with implementation details and results verified with the help of playtesting. | Limited to 3 as a way to carefully manage scope. |

| A baseline Work Breakdown Structure document for Rhythm Dice, at task level, with work estimates and broad category assignments (Art, Animation, Programming, etc.) | Will be instrumental to project planning. |

| A modified Work Breakdown Structure document for Rhythm Dice, with estimates that include the 3 chosen strategies implemented. | To provide quantitative scores for the effectiveness of the strategies. |

| Actual work spent also documented in the above. | To verify the above scores. |

Table 2. Original notes used to define the scope of materials supplementary to the game.

Retrospective

To improve oneself, one must be able to look back and critically assess their performance, mindful of practices that can be retained or improved upon.

As the first three weeks had passed, I had a look back at the sprint, using the familiar guiding questions from Scrum methodology (Scrum.org 2019):

- What worked well?

- What could be improved?

- What will we commit to doing in the next sprint? – actionable comments (e.g. SMART goals)

Falmouth University researchers Dr Alcwyn Parker and Dr Michael Scott have devised a model covering five domains for reflection, which can provide an additional dimension to the retrospective (Scott 2021):

- Cognitive – Knowledge, understanding, recall

- Procedural – Execution, production

- Affective – Identify and manage emotions

- Dispositional – Behaviour and management

- Interpersonal – Communication, conflict management

Finally, Smart Goals (Chen 2015) can be used to create commitments to the future which are:

- Specific

- Measurable

- Attainable

- Relevant

- Time-bound.

The table below shows the outcome of my retrospective session.

| Domain | What worked well? | What could be improved? | Commitments for next sprint |

| Cognitive | Used prior knowledge on ideation and planning; used the GDC vault to broaden view of art design in board games | I have not yet explored other areas specific to board game design | I will spend two evenings (six hours) next week learning about board game design from the University library, GDC talks, and other sources I can find. |

| Procedural | Rigorously documented my thoughts and findings in a OneNote notebook. | – | – |

| Affective | Used a quantitative approach for choosing the research question to break a stalemate | I could not maintain a consistent pace of work due to feelings of tiredness and burnout. | Whenever I feel burnt out, I will spend 15 – 30 minutes reading CBT Cognitive Behavioutal Therapy by Foreman and Pollard (2016). |

| Dispositional | – | I found it difficult to maintain a 3h/day, 6d/wk schedule. I spent less time planning the project than I hoped for. | By the middle of next week, I will have scheduled key dates and artifacts for Sprint 2, and have a WBS for a baseline version of Rhythm Dice. |

| Interpersonal | Established working relationship with supervisor, followed advice regarding next steps. | I could learn more by discussing research proposals with peers. | I am going to engage in discussion on the Canvas platform by writing at least one post and replying to two others. |

Table 3. Outcome of first sprint retrospective of the project, with SMART goals set for the next sprint.

I hope to repeat this exercise every sprint (three weeks).

References

CASTLE, Simon. 2020. “Board Game Types Explained: A Beginner’s Guide to Tabletop Gaming Terms.” Dicebreaker [online]. Available at: https://www.dicebreaker.com/categories/board-game/how-to/board-game-types-explained [accessed 12 Feb 2022].

CHEN, Huey-Tsyh. 2015. Practical Program Evaluation : Theory-Driven Evaluation and the Integrated Evaluation Perspective. London: Sage Publications.

FOREMAN, Elaine Iljon and Clair POLLARD. 2016. CBT, Cognitive Behavioural Therapy : Your Toolkit to Modify Mood, Overcome Obstructions and Improve Your Life. London Icon Books Ltd.

GOLDSCHMIDT, Gabriela and Ben MATTHEWS. 2022. “Formulating Design Research Questions: A Framework.” Design Studies 78(78), [online], 101062. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/356972825_Formulating_design_research_questions_A_framework [accessed 2 Feb 2022].

GRIMSBY, Gregory. 2021. “Board Game Design Summit: Art Direction for Board Games: Creating Compelling and Effective Visual Designs.” http://www.gdcvault.com [online]. Available at: https://www.gdcvault.com/play/1027077/Board-Game-Design-Summit-Art [accessed 12 Feb 2022].

SCOTT, Michael. 2021. “Continuing Personal Development. Domains.” Available at: https://flex.falmouth.ac.uk/courses/918/pages/reflection [accessed 13 Feb 2022].

SCRUM.ORG. 2019. “What Is a Sprint Retrospective?” Scrum.org [online]. Available at: https://www.scrum.org/resources/what-is-a-sprint-retrospective.

Games

Agricola [board game]. 2007. Uwe Rosenberg, Mayfair Games.

Caverna: The Cave Farmers [board game]. 2013. Use Rosenberg, Lookout Games.

Flick ’em up [board game]. 2015. Gaetan Beaujannot and Jean Yves Monpertuis, Pretzel Games.

Santorini [board game]. 2016. Gord!, Roxley.