One of the most important considerations for indie video game developers is managing the scope of their creations. Since development time and costs can ramp up quickly, and starting budgets can be as low as nil, developers have welcomed ways to downscope, by using pixel art, minimalist aesthetics, or in some recent cases, a tabletop-inspired look and feel for their digital games.

Luckily, tabletop game designers have already been writing about their experiences in an industry where the inclusion of a few extra game pieces can mean the difference between profit and loss. The subject is broader than simply streamlining aesthetics, as the physicality and directness of interaction with tabletop games creates additional constraints that can help focus the game’s mechanics.

Below is a list of considerations for digital game developers conscious of reducing their workload; those strategies are broadly divided into simplifying assets, streamlining mechanics, and responding to market expectations.

Control quality and quantity of assets

1. Use regular components

In tabletop game development, manufacturers offer regular molds for standard plastic components: pawns, round tokens, sand timers, acrylic gems and stones, discs, square tokens, stands and spinners. Wooden components may come in the shape of meeples, cubes, discs and triangles (Long Pack Games 2022). It took designer Cody Miller “more time, energy and resources to create pre-painted miniatures, than all the rest of the components in Xia combined” (2015). In the tabletop world, non-standard components could be prohibitively expensive, or even impossible to mass produce (Fristoe 2016).

Likewise, in video game development, creating complex assets translates to a longer development time. While asset stores address this, readily available assets may clash with the target art design. Simple shapes are abstract and universal.

Sources: LongPack Games, Stonemaier Games, Nothing Sacred Games

2. Limit the number of components

Tabletop designer/publisher Jamey Stegmaier of Stonemaier Games recommends planning components early in the design based on the target audience and retail price of the game (2020). In the context of an indie game, to sell at a low price point, game pieces need to be appropriately limited in number, detail or both. Board game designers can work with manufactures early on to get quotes for component prices.

JT Smith writes that when designing for publishing, the sky is practically the limit; the only strategic consideration being component material and quantity – “how few components you can use to keep the game playable, yet profitable” (2011).

When designing the $9.99 card game Light Rail to be produced using Print on Demand, Daniel Solis had to carefully limit the number of cards at 54, as each extra card would cut into his earnings per unit sold (2014).

In digital games, instantiating multiple copies of the same asset is trivial and free of the manufacturing costs associated with physical games. But scenarios where assets are unique (e.g. a roster of characters, or an item catalogue) are prime opportunities for downscoping.

Sources: 10 Steps to Design a Tabletop Game, Designing for Publishing, Daniel Solis Blog

3. Reuse art

Michelle Nephew writes: “Keep in mind that art is an expensive part of production, so if your game won’t suffer for using multiples of some cards, mention that to your editor in development” (2011).

This point follows logically from the previous two, but is worth reiterating when considering traditional art. The quote above considers reusing entire physical cards, which would reduce printing costs. Thankfully with video games, art is more easily separated from functionality, which gives the following benefits:

- Art already used in one context, e.g. a player pose, can be reused in a different context, e.g. an atlas entry, a card, or a menu background.

- If the context does not change, but variety is needed, digital art allows developers to tweak existing art by changing the lighting, post-processing effects, and even layer positioning to achieve this.

Source: The Kobold Guide to Board Game Design

Think about mechanics

4. Dynamic content focus – mechanics come first

Video games content may be static – where the quantity of content comes first, or dynamic – where mechanics come first. A dynamic design is more board-game like and enables replayability without the need to spend too much on content generation.

Source: How Board Games Matter

5. Convert continuous space and time to discrete spatial units and turn-based mechanics

This is a useful strategy when translating video game mechanics into a paper prototype (Ham 2016). Working in discrete dimensions greatly limit the possibility space. This simplicity should become evident when designing, testing and tuning only needs to consider a limited number of (usually integer-defined) game states, as opposed to the floating-point math and edge cases that come with it. This approach is suitable for many games (though not all).

There is a caveat, as modern game engines such as Unity and Unreal Engine assume that continuous space and time will be used out of the box, and require extra setup for elements such as grid-based logic or a turn system.

Source: Tabletop Game Design for Video Game Designers

6. Convert three-dimensional game space to two dimensions

Another strategy developed with paper prototyping in mind; working in two dimensions is simpler, and flat, square boards are a standard order for board game manufacturers, making this the most cost-efficient option. Again, the benefits of this for digital game development will depend on engine used.

Source: Tabletop Game Design for Video Game Designers

7. Constrain game by transparent grammar to prevent over-designing

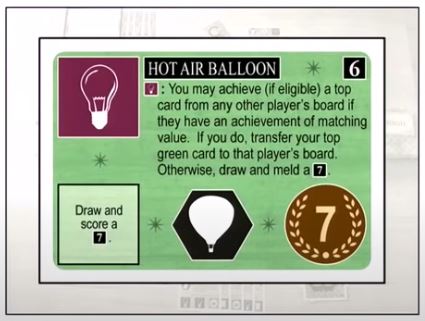

Soren Johnson (Civ IV, Offworld Trading Company) defines tabletop games not by their physical components, but by their transparency – their rules being completely known to the player (2015). To ensure players can grasp those rules, tabletop game designers can use self-imposed grammar to limit the possibility space. If a new element (e.g. card effect) cannot be expressed within that grammar, it is abandoned, therefore helping manage scope.

There is an added benefit: in a multiplayer scenario, transparent mechanics allow new players to learn by observing experienced players, reducing the need for manuals or tutorials.

Source: How Board Games Matter

Respond to the market

8. Consider a genre that lets you reduce focus on either mechanics, pieces/graphics, or story/theme

Rob Daviau writes about certain tabletop genres with uneven weighting of the above three elements. Roleplaying games favour story, are supported by rules, and can omit pieces and graphics. Eurogames favour rules, use minimal theming, and frequently reuse pieces. Abstract games omit the story, while miniature games focus on pieces. Wargames tend to require a more balanced weighting of all elements (2011).

If you want to design a Eurogame (…) your audience will not mind a light theme or generic cubes and meeples (Daviau 2011).

Source: The Kobold Guide to Board Game Design

9. Manage expectations

Game Lead Chalit Noonchoo of Gordian Quest writes that selling a card-based game as a digital game made was achievable for a small studio, as they were “less beholden to expectations like having triple-A visuals, tons of animations, or heavy cut scenes” (Winkie 2021).

Source: Wired

References

DAVIAU, Rob. 2011. “Design intuitively.” The Kobold Guide to Boardgame Design, pp.42-49.

FRISTOE, Teale. 2016. “Designing under Constraints.” Nothing Sacred Games [online]. Available at: http://nothingsacredgames.com/designing-under-constraints/ [accessed 28 Mar 2022].

HAM, Ethan. 2016. Tabletop Game Design for Video Game Designers. New York: Focal Press.

JOHNSON, Soren. 2015. “How Board Games Matter.” http://www.youtube.com [online]. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5xWNfVhVTJU [accessed 28 Mar 2022].

LONGPACK GAMES. 2022. “Plastic Components – LongPack Games.” LongPack Games [online]. Available at: https://www.longpackgames.com/components-board-games/plastic-components/ [accessed 28 Mar 2022].

NEPHEW, Michelle. 2011. Getting Your Game Published. The Kobold Guide to Board Game Design, pp.123-136.

SMITH, J.T. 2011. “Designing for publishing.” In Tabletop: analog game design (pp. 41-46). Available at: https://dl.acm.org/doi/pdf/10.5555/2031882.2031888 [accessed 28 Mar 2022].

SOLIS, Daniel. 2014. “Breakdown of POD Pricing.” Daniel Solis [online]. Available at: http://danielsolisblog.blogspot.com/2014/11/breakdown-of-pod-pricing.html [accessed 28 Mar 2022].

STEGMAIER, Jamey. 2015. “Legends, Lore, and Insights about Creating Pre-Painted Miniatures for a Crowdfunded Game.” Stonemaier Games [online]. Available at: https://stonemaiergames.com/legends-lore-and-insights-about-creating-pre-painted-miniatures-for-a-crowdfunded-game/ [accessed 28 Mar 2022].

STEGMAIER, Jamey. 2020. “10 Steps to Design a Tabletop Game (2020 Version).” http://www.youtube.com [online]. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VgEt7PysQgc [accessed 28 Mar 2022].

WINKIE, Luke. 2021. “Indie Video Games Have Finally Embraced the Tabletop Scene.” Wired [online]. Available at: https://www.wired.com/story/indie-developers-studios-tabletop-board-games/ [accessed 28 Mar 2022].

Games

Civilization IV. 2005. Firaxis Games, 2K Games.

Gordian Quest. 2020. Mixed Realms, Mixed Realms.

Innovation [board game]. 2010. Carl Chudyk, Asmadi Games.

Light Rail [board game]. 2014. Daniel Solis, FunBox Jogos.

Offworld Trading Company. 2016. Mohawk Games, Stardock.

Race for the Galaxy [board game]. 2007. Thomas Lehmann, Rio Grande Games.

Thief. 1998. Looking Glass Studios, Eidos Interactive.

Xia: Legends of a Drift System [board game]. 2014. Cody Miller, Far Off Games.

After some reflection, I should probably rename these to the following:

1. Use regular components.

2. Limit the number of components.

3. Reuse art.

4. Prefer emergent gameplay over set pieces.

5. Convert continuous space and time to discrete spatial units and turn-based mechanics.

6. Convert three-dimensional game space to two dimensions.

7. Constrain the game by transparent grammar to prevent over-designing.

8. Align with a genre with a favourable weighting of mechanics, graphics, and story.

9. Embrace tabletop themes in marketing.